“Give someone a fish and they eat for a day; teach someone to fish, and they can feed themselves and their relations for a lifetime”

– Chinese proverb, adapted here.

If you’ve ever tried to teach someone something, or been the student in a teaching moment, you’ll know that the idea of ‘teaching someone to fish’ may well be fraught with traps and wrong turns. Even if a teacher has the best intentions, teaching still requires skills and expertise along with a disposition to teach that includes an ability to connect with, understand and respect learners. If teaching someone to fish is more complicated than it first seems, how complex is supporting organisational development toward adaptability and sustainability? Such a supporting moment needs, of necessity, to be about the organisation rather than any supporters, coaches or funders of organisational development. This is an important lesson and one that seems to have informed the government’s investment in Whānau Ora organisations and collectives. In this post I want to explore some of the rationale for this endogenous development approach.

The first time I came across the idea of endogenous development was in the international capacity development literature, where in order for capacity development to lead to gains in organisational capacity, adaptability and sustainability it was clearly recognised that it had to be endogenous (Lopes & Theisohn, 2003). So what does endogenous mean? According to the capacity building programme Compas,

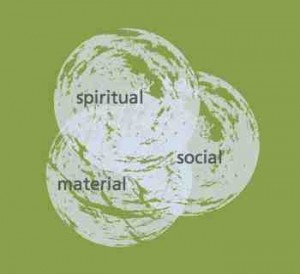

“Endogenous development is based on local people’s criteria for development and takes into account their material, social and spiritual well-being… The aim of endogenous development is to to empower local communities to take control of their own development process. While revitalising ancestral and local knowledge, endogenous development helps local people select those external resources that best fit the local conditions” (Compas, 2010, p. 2).

In a similar vein, Fred Chancey speaking at closing of the first national Indigenous Governance Conference in Canberra in 2002 (Reconciliation Australia, 2002, p. 4) noted that

“…there is compelling evidence that sustained and measurable improvements in the social and economic well-being of Indigenous people only occurs when real decision-making power is vested in their communities.”

For Māori Tino Rangatiratanga (sovereignty) and the Treaty of Waitangi are essential components of Māori development (Durie, 1994a,b, 2000). It is from this basis that Māori and Iwi organisations enter into partnership relationships with the Crown and its agencies. That is, a relationship that is, by its nature, fair, honest, reasonable and conducted in good faith. This is the foundation upon which endogenous development can proceed.

Lopes and Theisohn (2003), however, point out that defining organisational development as endogenous has implications for the cooperation of external agencies. Many external agencies are used to tagging the funding they provide to the goals they want to see achieved, with these goals often set without any close consultation or partnership with funded organisations. These goals may not be related to local priorities, or even to the concerns and issues affecting local people. And yet the need to funding to do some good in their communities may mean that organisations agree to abide by funding conditions and requirements, including the achievement of meaningless goals.

As researchers and evaluators working with Whānau Ora organisations and collectives we need to ensure that we’re knowledgeable about the rationale for endogenous development, including the potential outcomes of working in this way with organisations and collectives. We also need to be wary about the newness of this arrangement for government agencies that are inherently risk averse and possibly unused to partnering in this way with Māori and Iwi organisations. We need to be critically optimistic about the opportunities for Whānau Ora that are embedded in this approach – optimistic that these opportunities will come to fruition, and critical of government agencies and Whānau Ora organisations and collectives themselves as either enablers of, or barriers to endogenous development (Cram, 2005).

When endogenous Māori-led and controlled Māori development happens we might realise a vision of Māori development such as that proffered by Māori Land Court Chief Judge Joe Williams

“…my uri would still speak our language, they would still know and practice our tribal lore, and they would still, in a manner which makes sense to them in their time, draw spiritual strength from our lands, mountains and rivers. And, in addition to all of that, I would want them to be healthy, wealthy and wise.”

References

Compas (2010). Bio-cultural community protocols enforce biodiversity benefits – A selection of cases and experiences. Endogenous Development Magazine, 6 – July.

Cram, F. (2005). An ode to Pink Floyd: Chasing the magic of Mäori and Iwi providers. In Ngä Pae o te Märamatanga, J.S. Te Rito (Series Editor), ‘Ngä Pae o te Märamatanga – Research and policy seminar series’. Turnball House, Wellington, February 2005. Auckland: Ngä Pae o te Märamatanga.

Durie, M.H. (1994a). An introduction to the Hui Whakapūmau. In Hui Whakapūmau. Wellington: Ministry of Māori Development.

Durie, M.H. (1994b). Concluding remarks. Kia Pūmau Tonu. Proceedings of the Hui Whakapūmau Māori Development Conference, August 1994. Palmerston North: Department of Māori Studies, Massey University.

Durie, M.H. (2000). Concluding remarks. He Pukenga Kōrero, Kōanga, 6, 52-57.

Lopes, C. & Theisohn, T. (2003). Ownership, leadership and transformation – Can we do better for capacity development? London: Earthscan, and United Nations Development Programme.

Illustrations from Compas